In trying to explain differentiated responses to a mandatory national identification scheme in Britain that would rely on biometric technology, Martin and Donovan point to an interesting paradox in New surveillance technologies and their publics: A case of biometrics:

In contrast to some traditional conceptualizations of the relationship between public understanding and science, it was often those entities that best understood the technology that found it least acceptable, rather than those populations that lacked knowledge.[1]

I accidentally came across this scenario in Joseph Kamarū’s rendition of ‘Ūhoro Ūrīa Maiguire’ [The news they heard].[2]

In this literary artifact, techno-skepticism from the techno-aware publics was playing itself out back in the 1950s when freedom fighters urged their people to resist colonial office’s collection of exemplar prints.

Source: Ūhoro Ūrīa Maiguire. Mau Mau Songs Volume 2, Track 09, KCS/MAU/CD171 Recorded by Joseph Kamarū.

[From minute 01:28]

Marutūo marimainī nīmatūarirūo hau oficinī gūtheca irore.

Makīrega irore, magītūarūo Yatta na arīa angī Naikuru kūoherūo ithaka.

…

Mūtikanaherūo ūhoro njīrainī.

Kana mwītīkīre gūtheca irore.

Ihoto cia Gīkūyū nīcio ciatuīkire mwīgito wa Gīkūyū handū kīarūma.

English Translation

When they [freedom fighters] were arrested from their hideouts, they were taken to the colonial office for their fingerprints to be recorded.

They [freedom fighters] refused to voluntarily have their fingerprints taken and were taken to Yatta camp and others to Nakuru on land charges.

…

Be wary of roadside information (unverified) or allow them [colonial officers] to record your fingerprints as land agreements.

The justice of the Gīkūyū community became the community’s eternal shield.

More than fifty years later, Mau Mau veterans initially refused to use biometrics to register as voters, in fear of being ‘exposed’ by the technologies from their colonial resistance years. Though they went on to register, this fear of biometric technologies in voter registration was also apparent with former Mūngīkī adherents, who perhaps have a dark history to cover up, and not just radical consciousness as a public in civil discourse in Gīkūyūland.

The voices in the song further cautions against ‘roadside news’, perhaps what passes today for disinformation or ‘Fake News’ depending on your proximity to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

Biometrics, disinformation, and resistance - those words were as popular in 1950s colonial Kenya as they are in post-Nov 2016 American politics.

PS: As with all translation efforts, song meanings may not be as straightforward. If you have an alternative meaning to this song, I would be happy to hear from you: jambo [@] moseskaranja [.] com

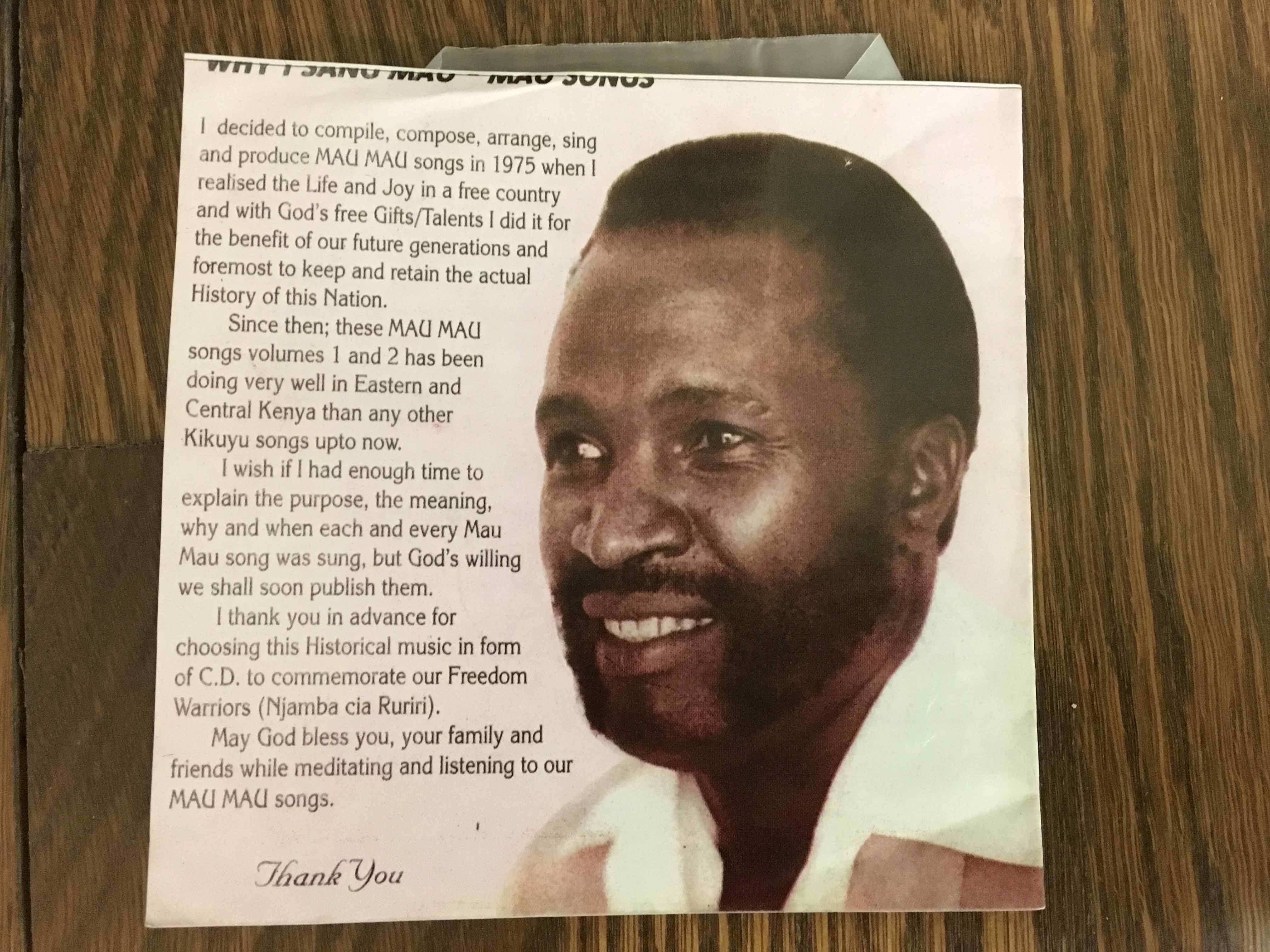

Back cover to Kamarū’s Mau Mau Songs Volume 2 album.

Footnotes

[1] Martin, A. and Donovan, K. (2014). New surveillance technologies and their publics: A case of biometrics. Public Understanding of Science, 24(7), pp.842-857.

[2] Ūhoro Ūrīa Maiguire. Mau Mau Songs Volume 2, Track 09, KCS/MAU/CD171 Recorded by Joseph Kamarū